Ada Lovelace And Charles Babbage Designed A Computer In The 1840s. A Cartoonist Finishes The Project

‘Surely there must be a couple of new Ada Lovelace lurking in this land?” exclaimed digital doyenne Martha Lane Fox last month, as she issued a call for women to turn their hands to tech – part of her new plan, dubbed Dot Everyone, for an internet-savvy nation.

It’s little wonder that the enigmatic daughter of Lord Byron has been put, posthumously, on a pedestal. Brought up to shun the lure of poetry and revel instead in numbers, Lovelace teamed up with mathematician Charles Babbage who had grand plans for an adding machine, named the Difference Engine, and a computer called the Analytical Engine, for which Lovelace wrote the programs. Then tragedy struck – Lovelace died, aged just 36. They never built a machine.

But now the mother of computing might finally have the chance to realize her own potential. As the eponymous stars of a new graphic novel The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage, the pair have been resurrected to finish what they started. “I guess it just seemed like a really stupid ending, that they didn’t build the machine,” says author Sydney Padua, a London-based computer animator. “Plus I really wanted to draw comics … and you can’t draw very good comics about dead people and their machine they didn’t build!” Having first illustrated the duo some years ago to mark Ada Lovelace Day, the annual celebration of women in science and tech, the comic’s huge popularity spurred Padua to develop the cartoons on her blog and ultimately unleash the book.

Exploring, then rejecting, the sad fate of Lovelace and her plans, Padua turns the tables on history, setting the aristocrat to work building a mechanical behemoth. The upshot is a pipe-smoking, jodphur-wearing steampunk technologist who would startle even Lane Fox. It doesn’t end there. Having built a technological masterpiece, a series of madcap escapades ensue in which Lovelace and Babbage are joined by a host of Victorian celebrities, from the ultimate client from hell, Queen Victoria, who demands the machine be used for fighting crime, to novelist George Eliot, who finds herself lost in its maze-like interior. “It really is very much about my own experiences in the labyrinth of computing,” says Padua.

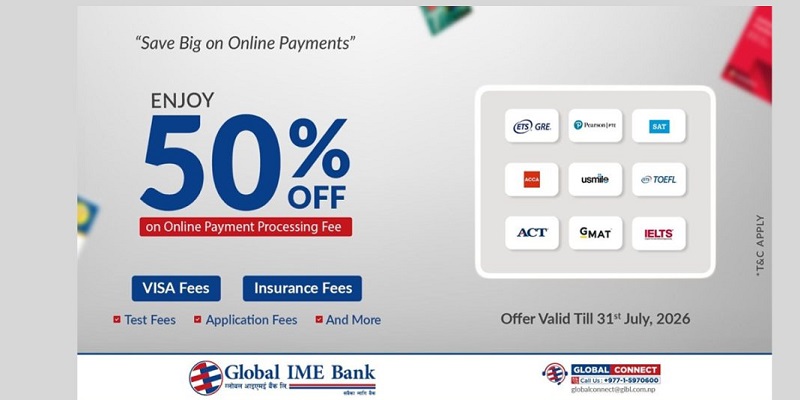

But if the reborn mathematicians find building a machine something of a handful, they aren’t alone. In trying to present an accurate depiction of the analytical engine for an explanatory appendix (shown here), Padua discovered there was little to go on, and found herself rifling through the work of Babbage scholar Allan Bromley for design clues.

“I just sat down, basically, with the Bromley papers and whatever of Babbage’s plans I could get my hands on through fair means or foul,” she says. The result is a shining feat of engineering that her dynamic duo would be proud of. A rip-roaring caper engulfed in footnotes of quotes, quips and illuminating asides (Babbage, Padua reveals, gained notoriety as the scourge of street musicians), the book does more than simply celebrate the genius of the first computer programmer, it encourages us to turn our imagination to technology – just as Lovelace did. And that’s an inspiration to us all.